Kanji? Aargh! Keigo? Help!

.

.

Last week, I wrote the article, 5 Reasons Why Japanese Is One of the Easiest Languages to Learn. You thought that was the end of the story? Sorry, no.

Despite highly organized grammar, easy-to-learn vocabulary, and the lack of impossible sounds or tones, Japanese can be a challenge to learn, especially coming from English. Here’s why.

.

・・・・・

.

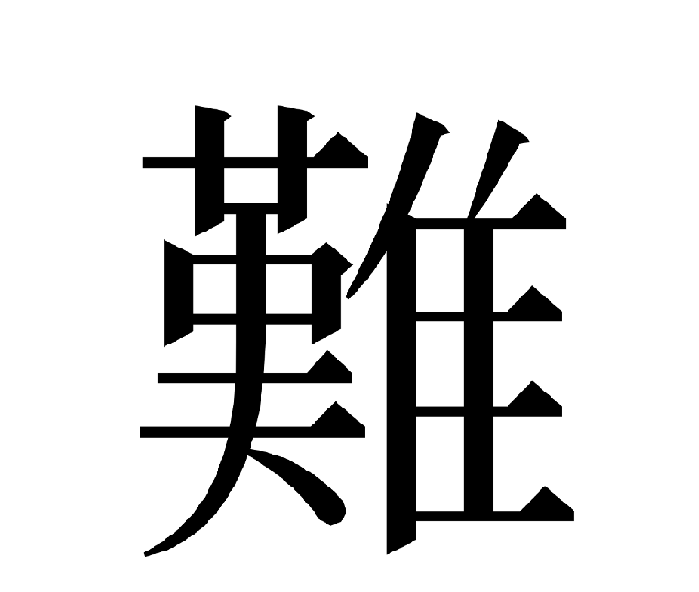

1. Kanji (漢字)

Most beginners think the problem with kanji is that there’s so many of them. Nope. You can go far with just 1000 kanji, read a newspaper with 1500, and complete the set with 2000. Contrast that with Chinese where you have to learn around 10,000 to write an email.

A thousand characters sounds like a lot, but they’re put together with component radicals that usually have some kind of logic that make them easier to remember.

But unlike Japanese grammar which is extremely regular, kanji is a complete disaster.

To start with, every kanji has at least 2 unrelated pronunciations and some characters have far more. 生 has 6 ways to read it. 下 has 8. Which one to use? It depends on context. Aargh. Even Japanese natives struggle to know the right way to read new words.

If that wasn’t bad enough, there are thousands of exceptions. My dictionary says the character for day, 日, has 4 regular pronunciations: Nichi, jitsu, hi (bi), or ka.

I love the word nichiyoubi (Sunday) 日曜日 because the character is read two different ways (nichi and bi) in the same word. And that’s just getting started.

The combination 昨日 for yesterday is kinou (unless you want to read it sakujitsu, which is okay too), 今日 for today is kyou (except when it’s konnichi), and 明日 for tomorrow is usually ashita unless it’s asu.

None of these pronunciations have anything to do with how the character is supposed to be read.

So, yeah, good luck with kanji.

.

2. Honorifics (Keigo 敬語)

Even in English, we speak differently with our boss than we do with our kids. Japanese takes this to an extreme with an entire extra set of words and verb conjugations for polite speaking.

To further complicate matters, there’s one set to speak of yourself humbly, and a different set to speak of your opposite honorably. There’s a set of rules for whether to use the humble or honorific that are so complex that new Japanese employees are given a day of training to learn how to speak to customers without making a language faux pas in their own language.

If Japanese native speakers can’t get keigo right, what hope do I have?

.

3. Three Words for Everything

Japanese vocabulary is an amalgam of old Japanese, old Chinese, and new English loan words. There’s 3 different words for just about everything.

A car can be a kuruma, jidousha, or kaa. Which to use? Depends on context. It’s kuruma when I want a ride, jidousha to learn at driving school, and kaa when I need a rental.

Should you say gyuunyuu or miruku for milk? Depends on which textbook you’re using.

.

4. Situation-Dependent Vocabulary

How do you say “I” in Japanese? Well…it depends on who you are and who you’re talking to.

There’s watakushi to be formal, watashi to sound like a textbook, boku for high school boys and now girls who don’t want to sound girly, atashi for girls who do want to sound girly, ore for guys who want to sound macho. There’s washi for old men, sessha to pretend to be a samurai, and wagahai to be an imperious cat.

How many different ways are there to say I? Though most are archaic or local dialect, this article counts 100.

But that’s not all! Depending on the situation from casual to formal, the verb and sentence tag also change.

When I started learning Japanese with the –desu/-masu form, as all textbooks teach (Kore wa pen desu), my Japanese friends were put off. They told me my Japanese was fine for the office, but if was going to speak that way with them, I’d be better sticking with English.

Is it pen desu, pen da, or pen de gozaimasu? All depends on the situation. It made me want to scream, “It’s a damn pen!”

.

5. Counters

In English, we say, “I bought a pair of pants.” Why not just, “I bought pants?” Who knows. Or, “Give me 3 sheets of paper and a slice of bread.”

We have the concept of counters in English, we just don’t use them very often.

In Japanese, every number is accompanied by a counter. There’s a counter for long cylindrical-shaped objects, a counter for round objects, and a counter for flat sheets.

There’s a counter for small animals, a counter for domesticated farm animals, a counter for fish, and a counter for birds that includes rabbits. There’s a counter for flight numbers, a counter for train numbers, a counter for train platforms, and a counter for the number of airplanes.

There are some amazingly specific counters like rin for the number of fish scales, aku for handfuls of solids like sand, which is not to be confused with kiku for handfuls of liquid. There’s a counter for pots, a counter for doors, and a counter for maps.

There are something like 500 different counters and you have to know which to use.

I once made the mistake of ordering koohii 2-mai instead of koohii 2-hai (2 sheets of coffee instead of 2 cups of coffee, but they sound very similar) at my neighborhood café. From that day on, whenever I went back to the café, the barista made a point of handing me my sheet of coffee.

.

6. Particles

30 years speaking Japanese and I still get particles wrong.

Particles are like prepositions. They attach to the noun but the right one to use depends on the verb.

Why is it densha ni norimasu to get on the train, but densha o orimasu to get off? Because it just is. There are some rules, but there’s no shortcut to learning them from usage.

.

7. Lack of Subject

In English, every sentence needs a subject if you don’t want Grammarly to scold you. In Japanese, the subject is left off if it’s obvious from context, and half the time when it isn’t obvious, too.

“My name is DC,” is usually translated as “Watashi no namae wa DC desu.” But that sounds like it came from a phrasebook. Japanese will simply say, “DC desu.” The “my name is…” part gets dropped. We know it’s your name so there’s no need to say it.

This makes Japanese very compact, and in writing, quite elegant. It’s wonderful for poetry. But regular conversation? Help!

Coming into the middle of a conversation is difficult. It’s especially challenging for non-native speakers since we don’t always catch every word. If I miss something at the beginning of the discussion, I may not have a clue what everyone is talking about until the conversation switches to a fresh topic.

.

8. Dialects

My favorite topic. Japanese classes and textbooks teach standard hyoujungo Japanese. But that isn’t what many people speak.

Each region of Japan has a different, distinctive dialect. Here’s my article on the Kansai (Osaka/Kyoto/Kobe/Nara) dialect.

If you live in Tokyo, hyoujungo is fine. But once you leave the confines of Edo, it’s almost a different language. TV news shows find it necessary to add subtitles when interviewing people from outside Tokyo.

If other Japanese can’t understand what they’re saying, what hope do we have?

Beyond the textbook itself, speaking Japanese naturally requires understanding Japanese culture. The correct response to “Do you speak Japanese?” Is “chotto dake” (Only a little) no matter how fluent you are. If you answer “Nihongo pera-pera” (I speak fluently), your Japanese may be perfect, but you’ve missed the subtleties of communicating with Japanese. Stay tuned for my article on that topic.

Japanese has some challenges, certainly, especially for native English speakers. But despite the complications, I believe it’s not a difficult language. It’s far, far easier than learning English, which has to be the worst possible language to learn.

I have absolutely no skill with languages and nearly failed Spanish classes in high school. If I was able to pick up Japanese, so can you.

All it takes is a chance to use it regularly and a bit of effort. So dig in. I guarantee it’s worth it.

Gambatte kudasai! 頑張って下さい!

..

.

『Learn Japan Deeply with DC!』

Writer: DC Palter

Read DC’s Stories More at Japonica Publication ( medium.com/japonica-publication )

(3/25/2022)

.

.

![[EVENT REVIEW & INTERVIEW] Highly acclaimed Japanese music artist Vicke Blanka performs in LA fo...](https://japanupmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/スクリーンショット-2024-02-26-午後2.05.04-150x150.png)