Japan’s Edo period (Edo jidai) lasted for 264 years and was characterized by economic growth, strict social order, isolationist foreign policies, a stable population, long-standing peace, and popular enjoyment of arts and culture.

By the mid-18th century, Edo’s (modern Tokyo) population had grown to over one million, likely making it the most populous city in the world at the time. But what accounted for this stable population despite the low birth rates and recurring famines?

For one thing, beginning in 1635, Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun of the Tokugawa dynasty, required the domanial lords (daimyo) to maintain households in the administrative capital of Edo and reside there for several months every other year. For another, the Tokugawa government enforced strict travel regulations on all of its citizens regardless of their social status.

We already know about the Sakoku (literally “chained country”) isolationist policy of the Edo period, which severely limited relations and trade between Japan and other countries. The policy banned nearly all foreign nationals from entering Japan while keeping common Japanese people from leaving the country.

The Tokugawa shogunate also controlled and limited every aspect of national travel to an extent unparalleled in the pre-industrial world. Ordinary Japanese citizens were mandated to obtain a permit to travel in and out of Edo.

Most features of the travel control system were put into place very early in the Edo period. Travel was confined to five roads known as the Gokaido, the busiest of which was the Tokaido (literally East Sea road), the road from Edo to Kyoto running along the southern coast of Japan’s main island.

The shogunate designated post towns along these roads. They also set up official inns at some of the towns to house the samurai traveling on official business, as well as the daimyo traveling between their domains and Edo. The system was set up for official use, but other travelers could also use the well-maintained roads without fear of being accosted by bandits. In fact, ordinary people traveled more frequently and easily along the roads of Tokugawa Japan than possibly any place on the globe.

These roads, however, were controlled through a system of fifty-three checkpoint barriers known as the sekisho, at which travelers had to show a permit to pass. The sekisho were implemented during the early part of the Edo period and were part of the shogunate’s framework to enforce peace at a time when the Warring States period was just ending.

The sekisho were spread out strategically to check for movements of troops and guns, as well as to stop the daimyo from removing their wives and children from Edo, where they were kept as hostages of the shogunate. The sekisho were surrounded by palisades and placed in areas that were difficult to pass. The checkpoints were surrounded by a network of villages tasked with watching the area for sekisho violators.

The sekisho system employed by both the shogunate and the domains kept an eye out for wanted criminals and samurai fleeing their domains. The system also kept peasants on their land and stopped samurai from traveling anywhere except on official business. The sekisho discouraged women from traveling by utilizing a far more complicated application process for women’s permits in comparison to men’s permits. Many sekisho did not even allow women to pass, instead funneling all female travel through the few sekisho that would inspect the women strictly to check if they matched the descriptions on the permits they were carrying. For instance, a sekisho would deny a woman passage if her hair was judged to be cut and her permit said it was uncut. This ensured that the women would stay at home when the men had to travel on business, meaning that families wouldn’t leave a domain for greener pastures.

Following the need for business travel, the next most common reason for travel during the Edo period was religious pilgrimage. As a matter of fact, Edo period literature is full of satire about pilgrims whose only religious practice was buying a handful of amulets at the shrine to prove they’d been there. Most pilgrims were probably serious in their devotion, but their visit to the shrine was usually a part of an enjoyable vacation. Among those who could afford it, vacations lasting several months, leisurely wandering around Japan from one famous sight to another, were quite common.

But the growing popularity of travel during the Edo period was mostly tied to prosperity. To travel, a farmer or merchant needed both money and the ability to leave home with their farm or business carrying on without interruption. So what happened if people could not obtain a permit, or could not afford to go on a religious pilgrimage? The practice of using an okage-inu (おかげ犬) became popular during the Edo period. An okage-inu was a dog that would visit the shrine on behalf of the individual.

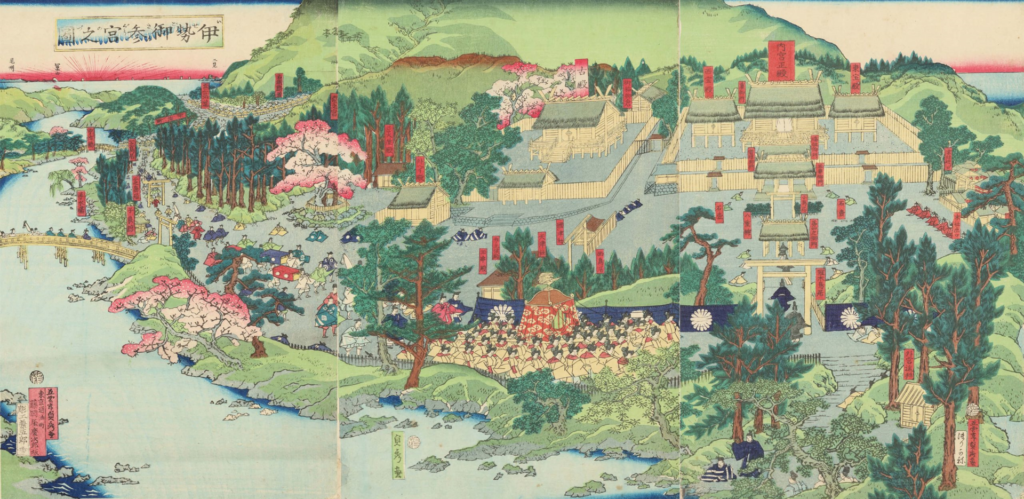

During the Edo period it was common for people to visit the Ise Grand Shrine, the most revered Shinto shrine in Japan. This once in a lifetime pilgrimage was known as okage-mairi. People of all classes would partake in this pilgrimage; however, some people were unable to make the trip for various reasons and instead sent an animal on their behalf.

For many, white dogs were the animal of choice, as they were deemed to possess a certain spiritual quality that made them the perfect choice for visiting the shrine. The dogs sent to Ise Grand Shrine were called okage-inu, and were often identified by the shimenawa straw ropes hung around their necks. They also carried bags containing money that was to be given to the shrine priest and go toward the care of the dogs during their journey. The roundtrip journey from Edo to Ise could take over one month, and the dogs relied on the kindness of strangers along the way.

There are stories of dogs traveling from all over Japan to the Ise Grand Shrine, receiving food and lodging, traveling with impromptu companions, and ultimately arriving back home with an amulet from the shrine.

『Kristine’s Eye on Japan: Introduction to Japanese Culture』

Writer: Kristine Ohkubo

.

(9/27/2022)