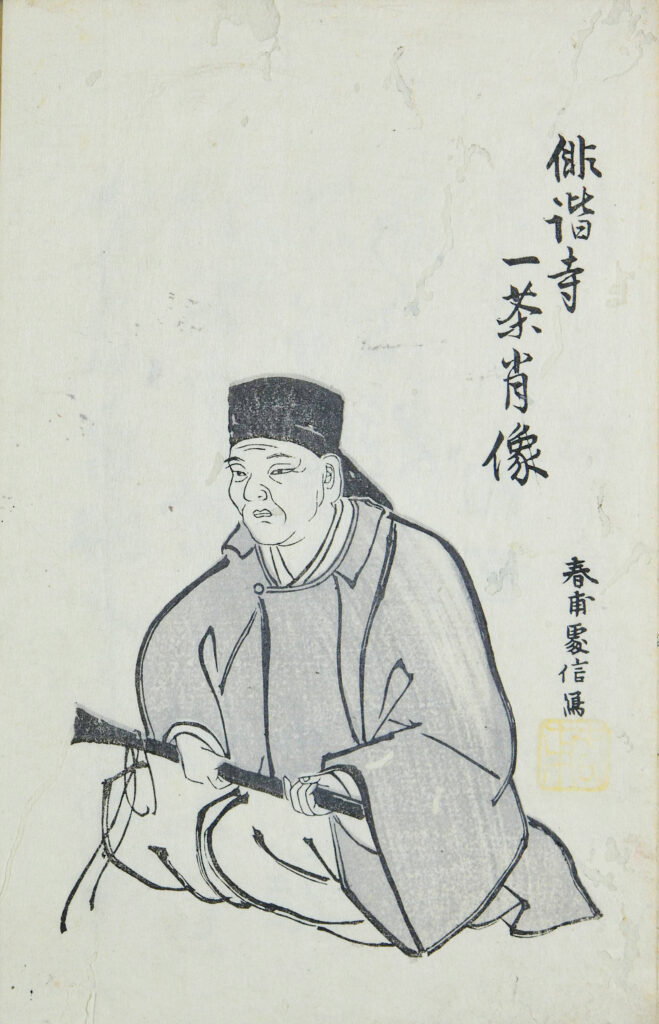

1763-1827

小林一茶

Issa Kobayashi

A Haiku Poet with a Heart for the Everyday

A Difficult Childhood

Issa Kobayashi, born in 1763 in Shinano Province (now Nagano Prefecture), lived a life marked by hardship and resilience. His real name was Yataro, and he came from a farming family. Issa’s early years were challenging. His mother passed away when he was just three years old, and his father remarried when Issa was eight. Unfortunately, his relationship with his stepmother was strained. She favored her own children, leaving Issa to care for his younger half-siblings. When the baby cried, Issa would be scolded, making him feel isolated and unloved. At the age of 15, his father sent him to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to work. Feeling abandoned, Issa despaired, believing that even his father had turned his back on him. However, his father’s decision stemmed from a desire to protect Issa from the toxic environment at home. This difficult upbringing shaped the emotional depth that would later become evident in Issa’s haiku poetry.

Finding Refuge in Haiku

In his early 20s, Issa spent time in Edo, where he began gravitating toward haiku poetry. At that time, haiku had become more simplistic and accessible, moving away from the highly refined aesthetic of “wabi-sabi,” which emphasized the beauty of imperfection and transience. Issa’s haiku embraced this more rustic, relatable style. His work reflected the everyday struggles of life—poverty, loss, fleeting joys—and was accessible to common people. His poems often focused on children, small animals, and seemingly insignificant moments of daily life, offering comfort and understanding to those who read them.

Travels across Japan

At 29, Issa returned briefly to his hometown, but his love of haiku soon drew him back to traveling. From ages 30 to 36, he journeyed across Japan, visiting the Kansai, Shikoku, and Kyushu regions. These trips were haiku pilgrimages, during which he met and studied under various poets, absorbing a range of haiku styles. Already an avid reader and diligent student, these travels broadened Issa’s poetic perspective. Kyoto, in particular, influenced him with its more free-spirited approach to haiku. His humble, accessible style directly reflected the people and poets he encountered. Upon returning to Edo, Issa refined his craft and became a mentor, guiding young poets and gaining recognition in haiku circles.

Inheritance Dispute and Financial Struggles

At around 39, Issa returned to his hometown to care for his ailing father. His father’s death, however, marked the beginning of a painful and prolonged inheritance dispute with his stepmother and younger half-brother. According to his father’s will, the family land and home were to be divided equally between Issa and his brother. However, tensions arose, partly because Issa had already received a sum of money when he left home as a teenager. His return after years away, and the fact that he had settled into the family home, angered his relatives. The dispute dragged on for nearly a decade, leaving Issa financially destitute. Despite these hardships, his poetic reputation continued to grow. By the time he finally reached an agreement with his brother and stepmother at age 50, Issa was already recognized as a haiku master.

Issa’s Troubled Family Life

Issa’s personal life was no less tumultuous than his financial one. At the age of 52, he married a woman 28 years younger, but their marriage was marked by tragedy. The couple had three sons and a daughter, but heartbreakingly, all four of their children died in infancy or early childhood. Issa’s wife also passed away young, at just 37, leaving him devastated. Despite these losses, Issa remained committed to his poetry, continuing to teach and publish haiku. His diary entries from this time reveal that, behind his tender and compassionate haiku, there was a man struggling with his own emotional turmoil. He often scolded his wife and was fixated on having children, pressuring her into repeated attempts to conceive. These elements of his character, contrasting with the gentle persona suggested by his haiku, offer a more complex portrait of Issa as a man.

His second marriage also ended in conflict, and Issa suffered a stroke in his later years, leading to partial paralysis and speech difficulties. Despite his declining health, he continued writing, although friends noted that his personality had grown more irritable. His final years were marked by physical deterioration, and in 1827, a fire destroyed his home. He spent his last months living in a small, cramped storehouse and passed away that November at the age of 65. His prolific haiku output—more than 20,000 poems over the course of his life—remains one of the most extraordinary legacies in Japanese literature.

Issa’s Haiku Style

Issa’s haiku are celebrated for their simplicity, humor, and compassion. His works often focus on small animals, such as frogs and sparrows, capturing the fleeting, everyday moments of life. Many of his haiku offer insights into the human condition, using humor to reflect on both suffering and joy. One of Issa’s most famous haiku reads, “Sparrow’s child, move aside, move aside—the horse is passing!” This poem describes a small sparrow chick, highlighting the fragility of life and the small, everyday dramas that unfold in the natural world. Another well-loved haiku, “Skinny frog, don’t lose heart—Issa is here!” reflects the poet’s own struggles and offers encouragement to a creature he identifies with. The accessibility of his haiku has made them beloved by both children and adults, ensuring his popularity endures even today.

Notable Works

One of Issa’s most well-known collections is Ora ga Haru (My Spring), published posthumously. This collection is named after one of his famous haiku: “Mediocrity is fitting enough—my spring.” The haiku reflects Issa’s acceptance of his simple, unremarkable life, finding peace in the ordinary rather than in grand or extraordinary experiences. Ora ga Haru chronicles Issa’s life at age 57, particularly the death of his daughter and the emotions that came with the changing seasons. Many of his haiku, such as “Snow is melting—the village is full of children!” capture the simple joys of life, while others, like “Come to me, little sparrow without a mother—let’s play together,” echo the sadness of his own childhood and the loss of his mother. His haiku continues to resonate with readers, drawing on universal themes of life, death, and human connection.

Issa’s Legacy

Though Issa was known during his lifetime, he did not gain widespread acclaim until the Meiji era. The poet Shiki Masaoka, who redefined haiku in the late 1800s, praised Issa’s works for their humor, compassion, and personification. Masaoka’s efforts helped elevate Issa’s status, placing him among the great haiku masters, such as Basho Matsuo and Buson Yosa. Today, Issa’s haiku is studied in Japanese schools as part of the curriculum, and his works continue to inspire both casual readers and scholars. His ability to find meaning and beauty in small moments, even amid personal hardship, ensures that his poetry remains beloved to this day.

.

.

.