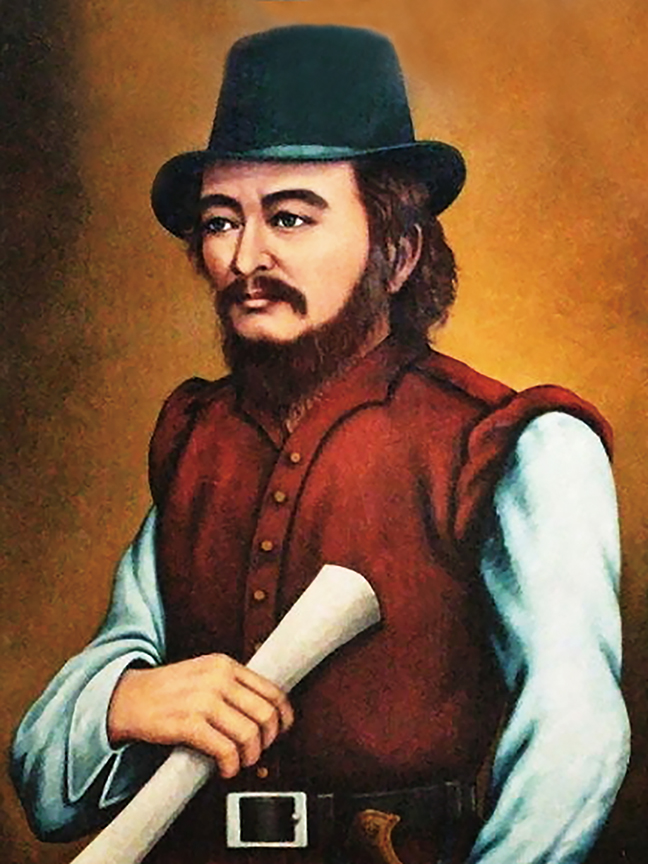

1564-1620

三浦按針(ウィリアム・アダムス)

Miura Anjin (William Adams)

The First European Samurai

In February 2024, an American historical drama series titled “Shogun” made waves in the United States as soon as it was released. The story is based on a true story of one European sailor, Willian Adams, who this article will be talking about. William Adams (Japanese name: Miura Anjin) was an English navigator, maritime pilot, and trader who worked as a diplomatic advisor to the Tokugawa clan in the early Edo period. He served as an interpreter and advisor during diplomatic missions and technical negotiations. His Japanese name was given to him by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the most powerful man in Japan at the time.

A Ship on a Mission Drifts to Japan After Being Shipwrecked

Born in 1546 in Gillingham, Kent, England, Adams lost his father, who was a sailor. At 12, he moved to London to become an apprentice shipwright. More interested in navigation than shipbuilding, Adams joined the Navy at 42 and served as captain of the supply ship Richard Duffield. He married in 1589 and had a daughter and a son.

At the time, experienced navigators were being recruited for a mission to expand trade from Rotterdam to the Far East. Adams and his brother volunteered and were hired as navigators on the ship Hoop. The grand voyage began in 1598 with five ships. Spain captured two of the five ships participating in this mission; one returned to Rotterdam after getting separated, and another sank. Only the Liefde vessel on which Adams was sailing survived the Pacific crossing. However, due to disease outbreaks and attacks, the crew was reduced from 110 to 24 by the time they reached Japan. Two years after the start of the mission, in 1600, the Liefde drifted to Kuroshima in what is now Usuki City, Oita Prefecture. Although helped by the leader of Usuki upon landing in Japan, they were detained, and their weapons were confiscated. Jesuit missionaries demanded the immediate execution of the Dutch and English, including Adams, but Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the most powerful figures in Japan at the time (equivalent to a king or emperor in European countries), did not execute them.

Why the Japanese Leader Did Not Execute Adams

Ieyasu summoned Adams and the crew to Osaka and flooded Adams with questions about world affairs. The questioning reportedly continued until midnight, indicating Ieyasu’s deep interest in Adams and his crew, given how busy he was with government affairs. Two days later, Ieyasu summons Adams and talks again. Did Ieyasu like Adams? It doesn’t seem so. Adams was subsequently confined for over a month. “During that time, I was anxious every day, thinking I would be crucified,” Adams later said. The Jesuits continued to argue for the execution of Adams and the sailors, claiming that “keeping Adams and the crew alive would be detrimental to Ieyasu and Japan.”

Still, Ieyasu replied, “For now, they have not harmed Japan, so executing them would be against reason and justice.”

Ieyasu Allows Adams to Meet with His Crew

Ieyasu summoned Adams for a third time. He again asked various questions, and as the interrogation neared its end, he asked Adams, “Would you like to meet your companions who were on that ship?” When Adams replied, “I would be delighted to,” Ieyasu said, “Then, let it be so.” Adams reunited with his companions after a long time, shedding tears. However, although Adams repeatedly begged to return to his homeland where his family was, Ieyasu forbade him from leaving the country.

Weapons on Adams’ Ship Changed Japanese History

In fact, Japan was in an unstable period at this time. In particular, 1600, the year Adams and his crew drifted to Japan, was the year of the “Battle of Sekigahara,” one of the largest and most famous civil wars in Japanese history. Samurai from across Japan were divided into Eastern and Western armies. Ieyasu was the leader of the Eastern army in this battle. Ieyasu used the cannons brought by Adams’s ship in battle for the first time in Japan and emerged victorious. This victory led Ieyasu to become the leader who unified Japan.

Gaining Ieyasu’s Trust as a Teacher and Shipbuilder

Adams, later, started to teach Ieyasu geometry, mathematics, and other subjects. Ieyasu, who was incredibly pleased, and a relationship of trust developed between Adams and Ieyasu. Ieyasu respected Adams as a teacher and accepted everything Adams told him. When the Liefde sank, Adams built Western-style sailing ships, completing an 80-ton sailing ship in 1604 and a 120-ton ship in 1607. For these achievements, Ieyasu granted Adams the title of Hatamoto, a high-ranking samurai with vast lands and privileges to serve him, along with the Japanese name Miura Anjin.

Adams Possessed the Samurai Spirit

Why was Adams, an English navigator, so beloved by Ieyasu and considered so important by the Japanese government at the time? Adams’ achievements, such as introducing Western navigation techniques, establishing diplomatic relations, imparting Western knowledge, and building Japan’s first Western-style sailing ships, all greatly influenced the strengthening of Japan’s diplomacy. For Ieyasu, who was advancing foreign policy, Adams was an essential asset. But that’s not all. Adams possessed the “Samurai Spirit,” which Ieyasu valued. Adams was intelligent and sincere. He wouldn’t accept things he disagreed with, even if ordered by superiors (like Ieyasu), and was consistently honest, even if it meant putting himself in a disadvantageous position. Adams spared no effort or hardship for others and always fulfilled his mission to the end. For Ieyasu, who made a point of surrounding himself with capable people, someone like Adams was undoubtedly someone he wanted as a close aide.

Choosing to Live as a Samurai

Ieyasu liked Adams and relied on him mainly for diplomatic matters. Ieyasu couldn’t afford to lose Adams and gave him good treatment to prevent him from returning to his home country. Later, Adams married a Japanese woman and had children. By this time, Adams had been granted permission to return home, and he had the opportunity to return to his homeland with an English ship that had come to Japan for trade. Still, he chose to stay in Japan. After Ieyasu’s death, trade restrictions were imposed in Japan, and Adams’ work decreased. Adams died at age 56, but his achievements are still celebrated today. Japan has numerous monuments and memorial parks for Anjin, and the Anjin Festival is held in his honor every year.

.

.

.