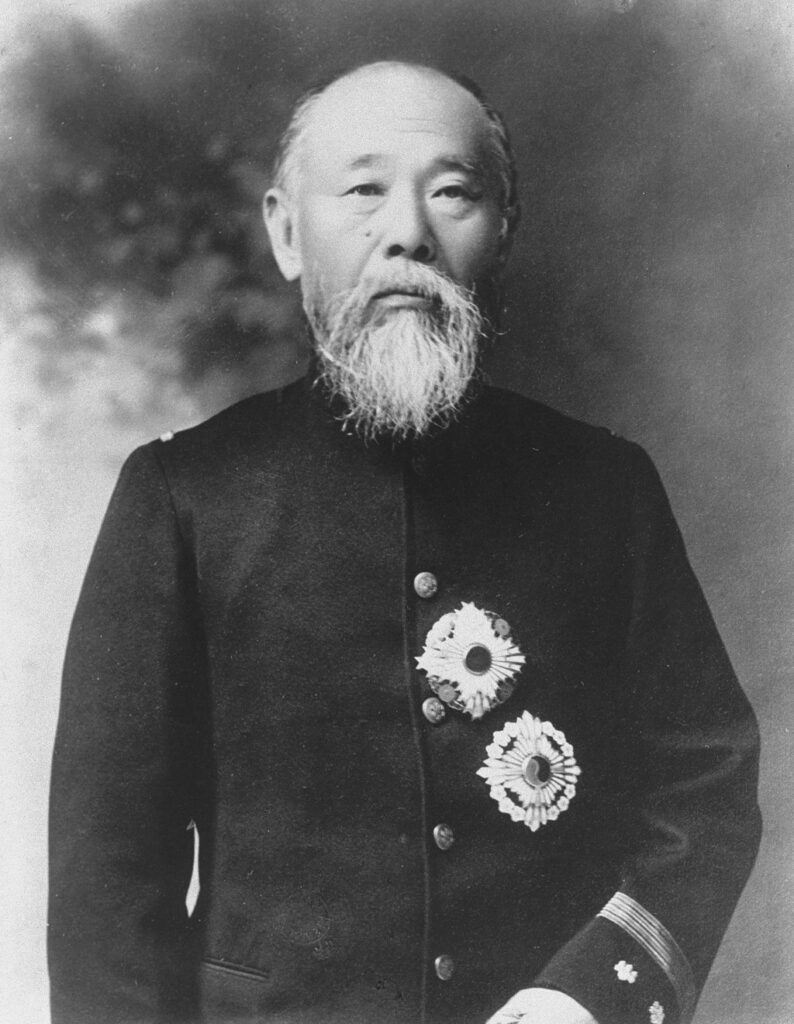

伊藤博文 ITO, Hirobumi

1841 – 1909

Learning the Importance of Learning and the Flexibly of Evolving the Beliefs You Hold

Birth and First Steps to Becoming a Politician

Hirobumi Ito was born in 1841 as the eldest son of a farmer in what is now the Yamaguchi Prefecture. At that time, Japan was a society based on hierarchy and status far beyond our imagination, and it was almost impossible to change one’s birth status. He was born rather into a low status as a farmer, but his father was adopted into the middle class, and fortunately, he himself was able to become a low-ranking samurai, although the middle class was still a very low status among the samurais.

When he was 15 years old, he entered the Shoukasonjuku (a private school) to study. His teacher, Yoshida Shoin, praised him for his “gentle nature and lack of arrogance,” and for his talent in politics because of his ability to mediate between people. He was also praised for his political talent because he was good at getting along with others.

At the age of 21, he participated in the burning of the British legation. The British legation was burned to the ground in the fire that they set. It is possible to describe his actions as a young man with a sense of crisis after witnessing a foreign threat.

The English Language Helped him.

Despite this, in 1863, at the age of 22, he secretly traveled to England to study under the pretext of evading the shogunate and let go of his hope for Japan to learn about Western civilizations. As a young man in his early twenties, he probably had conflicting feelings of anger and resentment toward foreign countries and a longing for the wide world. He learned English in London, and within a few months, he was able to hold conversations and read words.

In 1863, when he was studying abroad, the Anglo-Satsuma War broke out. Two months later, the Choshu clan bombarded foreign ships by order of the Imperial Court. When he learned of the bombardment of foreign ships by the Choshu domain in England, he rushed back to Japan, but war with foreign nations was inevitable, and the Choshu domain suffered a defeat at the hands of the combined fleet of England, France, the United States, and the Netherlands in Shikoku. It was Hirobumi who served as an interpreter for the peace at this time.

As a result, he witnessed the prosperity of Shanghai and England through his study in Japan and shifted from the idea of expelling foreigners from Japan (expulsion of foreigners) to a more open-minded stance on Japan. To abandon a view to which one had once been committed and to switch views based on new experiences and lessons learned is an important attitude not only at the end of the tumultuous Tokugawa Shogunate but also in the modern era.

It was precise because he was flexible enough to change his way of thinking depending on circumstances, even if it was something he firmly believed in, that he was able to study in England and acquire English language skills at an early stage.

Within the Meiji government, he was highly regarded for his English language skills, and in 1871, at the age of 30, he visited Western countries as a member of a delegation. His purpose was to study the German Constitution. The government ordered him to conduct research on constitutions in foreign countries. Then, in 1885, he established the cabinet system and became the Prime Minister.

The Meiji Era and His Achievements

In the Meiji Era, he served as a councilor, the minister of industry, and the governor of the Hyogo Prefecture. After the important figures of the Meiji Restoration passed away, Hirobumi became a central figure in the government. He played a key role in leading Japan to modernization.

In 1885, at the age of 44, he became the first Prime Minister of Japan, as the youngest person to hold this position. He showed further achievements by being elected again a total of four times as Japan’s fifth, seventh, and tenth prime minister. And in addition, he also created the Meiji Constitution. It is said that he was able to become Japan’s first prime minister because of his ability to speak English. At the time, the number of Japanese people who could speak foreign languages was very low, so someone like Hirobumi, who was capable of speaking English, was extremely valuable.

The Constitution led by him was promulgated in 1889. The Constitution promulgated at that time was the “Constitution of the Empire of Japan,” which conveyed that the Emperor ruled as the head of state.

He was able to achieve high status within the Meiji government after the Meiji Restoration because of his English language skills. There is no doubt that his mastery of English before the Meiji Restoration had a significant positive impact on his life and his later political life. And also, due to his proficiency in English, he was able to go to Europe to study the Constitution as a member of the Iwakura Mission.

But, his greatest achievement, above all, was the enactment of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan. In order to find a constitution suitable for Japan in the Meiji era, he traveled to Prussia (today’s Germany) to learn from scholars. Along with leading Japan to a victory in the Sino-Japanese War with China.

In addition, he enacted a law called the Currency Law, which established the yen, the unit of money in Japan today, promoted industrial development and fostered Japanese industry, and built a railroad from Shimbashi in Tokyo to Yokohama in Kanagawa Prefecture.

It was Hirobumi who established a law called the “Education Ordinance,” and also made efforts to popularize education for women, which is now a norm.

If the Constitution and the Cabinet are the pillars of the nation, the economy, transportation, and schools are the pillars of society. These achievements, successfully left by him, made ever-lasting effects on our human history.

Learning from Hirobumi Ito

In simple words, Hirobumi Ito can be described as an all-powerful politician who could do anything. However, he was not just a pompous person; he also had a friendly side that took walks around his house and talked with the local townspeople. What we can learn from him is his flexibility to learn from his own actions and being open to changing his way of thinking.

However, he died in 1909, assassinated by a young Korean man at Harbin Station in China. It is said that he was such a gifted politician that if he had not been assassinated, the subsequent situations in Asia, including Japan, might have changed.

.

.

.

.