Japanese New Year Decorations and Their Origins

In Japan, New Year’s Day (January 1st) is the most important holiday of the year. Similar to Thanksgiving in the United States, families gather to celebrate the start of a new year. As part of these celebrations, special seasonal decorations are prepared. These include shimenawa (sacred ropes made of braided straw), kadomatsu (decorations made of pine and bamboo), and kagami mochi (decorative rice cakes). Each of these has a significant meaning and role, but in this article, we will focus on shimenawa.

In Japan, many people follow Shinto (one of Japan’s two main religions, rooted in traditional Japanese beliefs), which embraces the idea of yaoyorozu no kami (the belief in countless gods and deities). During the New Year, Japanese families welcome a special deity known as Toshigami-sama (Year God) into their homes. To ensure that Toshigami-sama has a pleasant stay, families thoroughly clean their homes to remove impurities. However, simply expelling impurities from the house is not enough. If left unattended, those impurities could re-enter the home. How can we maintain a purified space? The solution lies in hanging a shimenawa at the entrance of the home.

A shimenawa serves as a sacred boundary, separating the outside world from the inside of the house. Its primary function is to prevent external impurities from entering the home, creating a purified and welcoming space for Toshigami-sama.

The origins of shimenawa trace back to ancient Japan and are believed to stem from the term shirikumewana, mentioned in Kojiki (the oldest historical record of Japan). According to the story, a major event occurred when the sun goddess Amaterasu-Omikami hid herself inside a celestial cave, plunging the world into complete darkness. Chaos ensued as malevolent spirits roamed freely, bringing disaster to the world.

To resolve this crisis, the gods gathered and devised a plan. Each god contributed their unique skills: one orchestrated the strategy, another performed a sacred dance, while others crafted mirrors and jewels. Together, they succeeded in coaxing Amaterasu-Omikami out of the cave. Once she emerged, the gods quickly hung shirikumewana across the cave entrance to ensure she could never retreat into it again.

Today, this legend is preserved at Amanoiwato Shrine in Takachiho Town, Miyazaki Prefecture, where it is said the events of the story took place. Every year, on the winter solstice—the day when the sun’s power is weakest—there is a sacred ritual to replace the shimenawa at the shrine. This act symbolizes the renewal of the shimenawa‘s divine power, ensuring the sun goddess will not hide herself again.

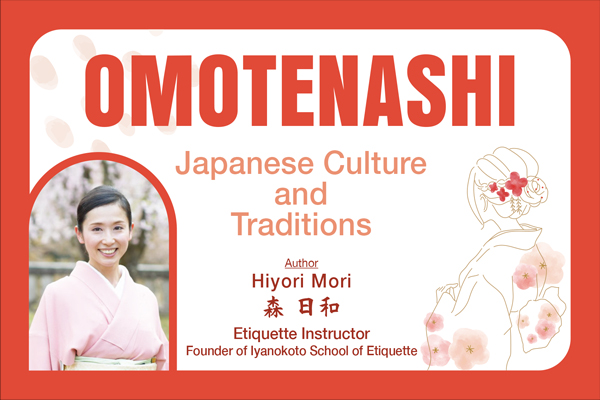

Author: Hiyori Mori (森 日和)

Founder of Iyanokoto School of Etiquette

Etiquette Instructor

After graduating from Kyoto Women’s University Junior College, Hiyori Mori worked as a CEO secretary at a travel agency while studying at the Kansai Branch of the Ogasawara School of Etiquette. Under the direct tutelage of Shinsai Yamamoto, the 32nd headmaster of the Ogasawara family lineage, she earned her instructor certification.

In 2009, leveraging her experience as a secretary, she began her career as a manners instructor. Since 2022, she has been actively involved in upcycling discarded kimono to preserve traditional Japanese garments, promoting circular economy initiatives, and sharing Japanese culture internationally.

Website: https://www.iyanokoto.com