40 Years in the Tire Industry

“Failure is not failure. It’s only failure if you give up.”

Graduating from a prestigious national university and landing a job at a top-tier Japanese trading company, Tomo Mizutani started his career traveling to over 40 countries in his twenties to manage export operations. Later, he turned around a near-bankrupt U.S. company, transforming it into a global enterprise with over $1 billion in revenue. At first glance, his story might seem like a tale of elite privilege and easy success. However, this is not a story of a corporate prodigy effortlessly rising to the top. It is one of grit and determination—a journey marked by battles with global economic challenges, tireless effort, and even moments where his very life seemed at stake. Mizutani’s story is one of overcoming limits and navigating the fine line between breaking and breakthrough. It leaves us with much to reflect on and draw inspiration from.

BIO:

Tomoshige MIZUTANI (水谷友重)

Chairman & CEO, TOYO TIRE HOLDINGS OF AMERICAS INC.

Born in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, Tomo Mizutani graduated from Kobe University’s School of Business Administration. He began his career in 1984 at Nissho Iwai Corporation (now Sojitz Corporation), where he specialized in the export of mining tires, traveling to over 40 countries worldwide. In 1992, he was tasked with revitalizing the Nitto brand and relocated to the United States. He joined TOYO TIRE Corporation in 2000 and became President of Nitto Tire U.S.A. Inc. in 2005. In 2011, he was appointed as an Executive Officer of TOYO TIRE Corporation and currently serves as Chairman & CEO of TOYO TIRE HOLDINGS OF AMERICAS INC.

Awards:

- Special Congressional Recognition for Outstanding Business Leadership (2013)

- International Citizen Award from the Japan America Society of Southern California (2014)

Speaking Engagements: Tomo Mizutani has delivered lectures at various prestigious institutions, including USC MBA, UCLA MBA, UCI, United States Air Force, Chapman University, Clemson University, Pepperdine University, Loyola Marymount University, and Harvard Business School Alumni events (New York, Dallas Petroleum Club, and various locations in Southern California), among others.

Lessons from a Young Trading Professional: “Learn by Watching”

In the 1970s, in the hills of Kobe, Japan, young Tomo Mizutani would walk down steep slopes on his way to school. The sprawling port of Kobe came into view each morning—a mundane yet vivid memory that remains etched in his mind.

“My hometown of Kobe is surrounded by mountains and the sea, with many hills,” Mizutani recalls. “Every day on my way to school, I could see the port of Kobe, bustling with container ships. Looking at those ships, I used to think, ‘If I got on one of those, I could go to faraway places. I’d love to see the world someday.’”

That dream grew clearer with time: “I wanted to work in international trade and sell goods overseas.”

After graduating from Kobe University, Mizutani joined Nissho Iwai Corporation (now Sojitz Corporation) in 1984, a company with strong local roots in Kobe. During Japan’s booming 1980s, trading firms like Nissho Iwai thrived as they supplied products and services to global markets, playing a pivotal role in the burgeoning global economy. These firms were both a gateway to exciting opportunities and highly competitive workplaces. Young professionals in international trade, in particular, were envied for their access to overseas markets and high-stakes negotiations.

Eager to dive into this world, Mizutani found himself assigned to the back office rather than the international trading department he had dreamed of. For three years, he tirelessly worked to secure a transfer and was eventually reassigned—but to a tire division that barely interested him. With just three members tasked with handling the global tire market, Mizutani began a grueling schedule.

“At the time, communication with international clients relied on Telex machines—a laborious process. Typed messages were sent to a dedicated department for transmission, while incoming messages, printed on long rolls of paper, were meticulously cut, sorted, and distributed each morning. The office handled everything from tires and automotive parts to Nike sports goods, tobacco, carpets, and more, with each employee juggling enormous workloads.

Photos: Recipient of the “International Citizen Award” from the Japan America Society of Southern California, Mizutani delivers his speech at the award ceremony.

“No one had the time to teach a newcomer like me,” Mizutani admits. “The mantra was ‘Learn by watching.’ Every morning, I would come in early and study the Telex communications of the most capable senior employees. Those were my textbooks.”

Do It or Don’t: “If You Do It, Do It Thoroughly”

The Secret to a 100% Success Rate

After joining one of Japan’s leading trading companies, Tomo Mizutani spent his twenties traveling to over 30 countries to manage export operations. Later, he turned around a struggling U.S.-based company on the verge of bankruptcy, transforming it into a global tire enterprise with over $1 billion in revenue. Mizutani’s journey has been one of constant challenges, straddling the line between breaking limits and making breakthroughs, as he forged ahead in life.

From Back Office to Global Sales

When Mizutani first joined the company, he was assigned to the back office. However, he harbored a strong desire to work in international sales. At the time, large Japanese trading firms were described as handling everything “from ramen to missiles,” emphasizing their wide-ranging operations. Employees had no say in their assignments, but Mizutani persistently lobbied for a transfer to the sales department. Eventually, his efforts paid off, and he was reassigned to the tire division—a field he had no knowledge or interest in at the time.

Responsible for “The Rest of the World”

Mizutani’s dream of joining the sales department finally came true, but his assignment was far from glamorous. He was placed in charge of tire exports, covering every region except for the U.S. and Cuba. The department was small, with just two employees managing the global market. While his colleague, fluent in Spanish, handled the U.S. and Cuba, Mizutani was tasked with overseeing the remaining regions, including Turkey, Zaire (now Congo), South Africa, and Northern Europe, within a year.

Discovering the “Treasure Map”

Nowadays, a quick Google search could yield a comprehensive list of mining operations worldwide. Back then, however, there was no such data readily available. Determined to find a solution, Mizutani explored internal company resources, visited mining-related organizations, and combed through library archives. Finally, he stumbled upon a detailed directory listing mining operations globally.

“It felt like I had discovered a treasure map,” Mizutani recalls. “I was so thrilled I could barely contain my excitement.”

The Harsh Realities of Mining Operations

“At mining sites, veins of ore are pursued deep underground, sometimes reaching depths of up to 1,000 meters,” Mizutani explains. “Open-pit mines are massive, resembling an inverted Mount Fuji. From above, even the enormous mining trucks operating below look like tiny specks.”

He describes the intense environment: “Every day, dynamite blasts are used to break apart the hard rock. The flash of light is followed by an explosive boom, and then a ground-shaking vibration reverberates through your body. It felt like being on a battlefield, with warning sirens constantly blaring in the background.”

Expanding to the World’s Mines

In the 1970s, China’s mining technology was far from adequate. By the 1980s, advanced technologies from Japan and other developed nations began to be introduced. At the time, Chinese mines lacked the knowledge and equipment for efficient open-pit mining, such as large trucks and excavators. Instead, countless coal mines across the country relied on dangerous underground mining methods, which claimed tens of thousands of lives annually.

To address this dire situation, projects were initiated with the help of foreign aid from developed nations to introduce safer open-pit mining techniques. Mizutani seized the opportunity to bid on these newly launched projects.

China possesses the world’s largest coal reserves. Leveraging these abundant resources, national policies were implemented to develop coal mines and provide the electricity necessary for economic growth. This surge in development also led to a rapid increase in demand for large mining tires.

“In selected coalfield development regions, entire towns were built from scratch, including roads, housing, schools, and other essential infrastructure. Water supply systems were installed, power plants were constructed, and large mining trucks were deployed. Once mining operations began in earnest, replacement tires became necessary, driving significant tire sales. As large-scale coal mines started operating one after another, the revenue generated from tire sales became substantial.”

“Securing contracts in countries I visited for the first time was the result of exhaustive preparation beforehand. Even for complex cases, I made every effort to approach negotiations by imagining the client’s needs from their perspective.”

“‘Do it or don’t. If you decide to do it, do it thoroughly.’ This philosophy is what I developed during that era through countless trials, errors, and experiences.”

About TOYO TIRES

TOYO TIRES is a brand driven by unique ideas and proprietary technology, striving to deliver “excitement and surprise that exceeds expectations and satisfaction.” The company aims to bring drivers their ideal driving experience. Its product lineup includes a full range of tires, from passenger vehicle tires to light truck tires, as well as tires for trucks and buses.

A Young Man in His 20s, Traveling to 30 Countries

After joining one of Japan’s largest trading companies, Tomo Mizutani spent his twenties traveling to 30 countries for export operations. Later, he turned around a U.S.-based company on the brink of bankruptcy, transforming it into a global tire enterprise with over $1 billion in revenue. Mizutani’s life has been defined by constant struggles, navigating the fine line between breaking limits and making breakthroughs as he forged his path forward.

Approximately 30 countries—that’s the number of places Mizutani visited in his twenties as a young trading company employee, traveling abroad to sell tires. Even for employees at major trading firms, it was typical for junior staff in their first few years to focus on domestic tasks or accompany seniors on business trips abroad. Traveling solo across the globe multiple times a year was an extraordinary case.

What set Mizutani on such an unconventional career path was the significant influence of his mentor, Mr. Nakashima, a respected superior.

In Mizutani’s words, “In the company, there were very few young trading professionals like me who traveled the world alone for work, even at a general trading firm. This sparked a lot of noise and friction among colleagues, with people asking, ‘Why is that young guy getting such special treatment?’” He recalls how Mr. Nakashima defended him, saying, “Mizutani is securing contracts during his trips abroad. What’s wrong with sending him overseas if he’s delivering results?”

-1.jpg)

Mr. Nakashima, Mizutani explains, was an old-school mentor who believed in the philosophy of “figure it out yourself” rather than giving direct instructions. “Thanks to him, I learned how to think critically, navigate trial and error, and persevere without giving up, even when faced with challenges or setbacks,” he adds. Despite the criticism Nakashima faced for disrupting company norms, he gave Mizutani numerous opportunities without hesitation, shaping the foundation of his career.

The Mentor Who Unlocked My True Potential

Meeting Mr. Nakashima was a turning point in Mizutani’s life, providing him with invaluable opportunities and dramatically changing his trajectory. “Looking back now, I realize how important compatibility with your company and colleagues is. Every company has its unique culture, and in my case, the culture at Nissho Iwai Corporation suited me well.

“But of course, in a large organization, you’ll sometimes encounter bosses you just can’t get along with. It’s incredibly tough when you have a completely incompatible superior. I’ve seen many people who quit their jobs out of frustration because they couldn’t adapt to their bosses or the company.

“What matters most, I think, is how you spend those tough times. No matter how challenging it is, you need to avoid becoming bitter. Instead, focus on finding the effort you need to make at that moment and keep pushing forward. It’s about preparing yourself for the time when a transfer or a change in environment turns things around.

“Throughout my career, I’ve worked under many different types of bosses. When I was biting the bullet, working hard despite the harsh criticism and gossip around me, I was fortunate to serve under Mr. Nakashima. He was the one who saw potential in me and gave me an incredible opportunity. Thanks to that encounter, I was able to shed the label of being a ‘slowpoke’ and become the person I am today.”

A Salesman Heading into the Battlefield

Let’s return to the story of Mizutani’s travels to 30 countries. The ability to “persevere through setbacks and never give up, even in dire situations,” which he previously mentioned, was honed through his overseas assignments. Many of the places he visited were dangerous countries embroiled in civil wars or extreme poverty. The business opportunities that landed on the desk of his small tire division were often in regions where other companies hesitated to venture. Going on these trips was less about business travel and more akin to stepping onto a battlefield.

Mizutani recalls his first overseas business trip to Sudan, a country in northeastern Africa. Its capital, Khartoum, was considered one of the most dangerous places in the world at the time, as well as a high-risk malaria region. “Originally, I was supposed to arrive in the early afternoon, with a car arranged to pick me up at the airport,” he says. “However, due to a flight delay, I missed my connecting flight and had to scramble to find an alternative. I finally arrived in Khartoum at 3 a.m.”

At the airport, he faced another challenge. The taxi drivers shouting “Taxi! Taxi!” seemed highly suspicious. “It felt like getting into one of their cars would lead to abduction,” Mizutani shares. Exhausted after more than a day without sleep—having bought a cheap ticket in Hong Kong and negotiated alternative flights in Rome, Athens, and Cairo—he weighed his options. Staying at the open-air airport risked contracting malaria, but taking a taxi was no less dangerous.

Finally, he made the fateful decision to get into a taxi. As the vehicle drove along pitch-black roads, relying only on its headlights, Mizutani braced himself for the worst. “A gun barrel was pointed at me through the open window,” he recalls. “At that moment, I thought, ‘If I disappear now, no one will ever know what happened.’ But then I heard someone shout, ‘Passport!’” To his relief, it was a military checkpoint.

This intense experience was just one of many. “I encountered situations where guns were pointed at me multiple times during my business trips,” Mizutani reflects. These moments taught him to stay composed and focus on the task at hand, even under extreme pressure.

To be continued in the next issue

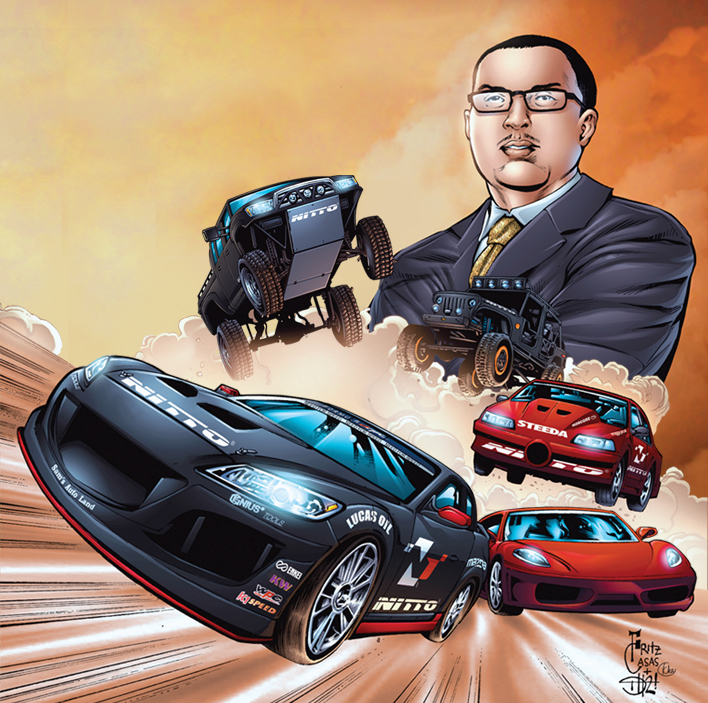

Explore the Nitto Tire Story in Web Comic Format

In addition to this article, you can enjoy the story of Nitto Tire through an engaging web comic. Click here to start reading!