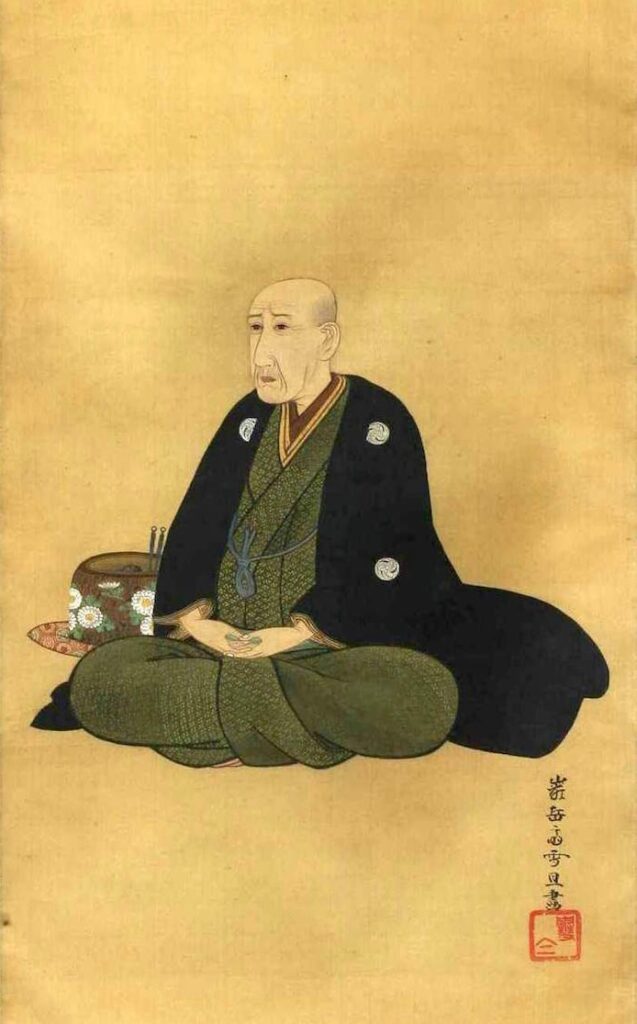

1767 – 1848

曲亭馬琴

Bakin Kyokutei

An Edo-Period Novelist Known for Timeless Tales

Name: AKA Bakin TAKIZAWA 滝沢馬琴, Pen name Kyokutei Bakin 曲亭馬琴, later called himself Toku (解), Original name is Okikuni Takizawa 滝沢興邦

From Samurai to Storyteller: The Journey of Kyokutei Bakin

Born in 1767, Bakin KYOKUTEI (real name Okikuni TAKIZAWA) came from a samurai family. His early years were marked by privilege, but his life took a dramatic turn when his father passed away at the age of nine. With his older brothers moving on—one to work for another family and the other adopted by relatives—Bakin inherited the family name but found himself in a difficult position as an attendant for a noble child. The child was cruel, subjecting him to bullying and violence, which eventually drove Bakin to run away at 14. He briefly aspired to become a doctor, but his true passion lay elsewhere. Immersed in books, Bakin began to pursue writing, and at 24, he met the artist and writer Santo Kyoden, marking the beginning of his literary career. This shift led Bakin to renounce his samurai status and dedicate himself fully to writing.

Breaking Boundaries: Establishing a Writer’s Life

By the time he turned 30, Bakin had left his position at a bookstore and married into a family that owned a geta (traditional Japanese sandal) shop. As the business declined, Bakin transitioned to writing full-time, adopting the pen name “Kyokutei Bakin.” Known for weaving a strong sense of justice and mystical themes into his stories, he became one of the few professional writers of his time. In an era when most authors wrote part-time, Bakin blazed a new trail, introducing a system of payment per book and per manuscript page, effectively establishing the profession of full-time writer in Japan.

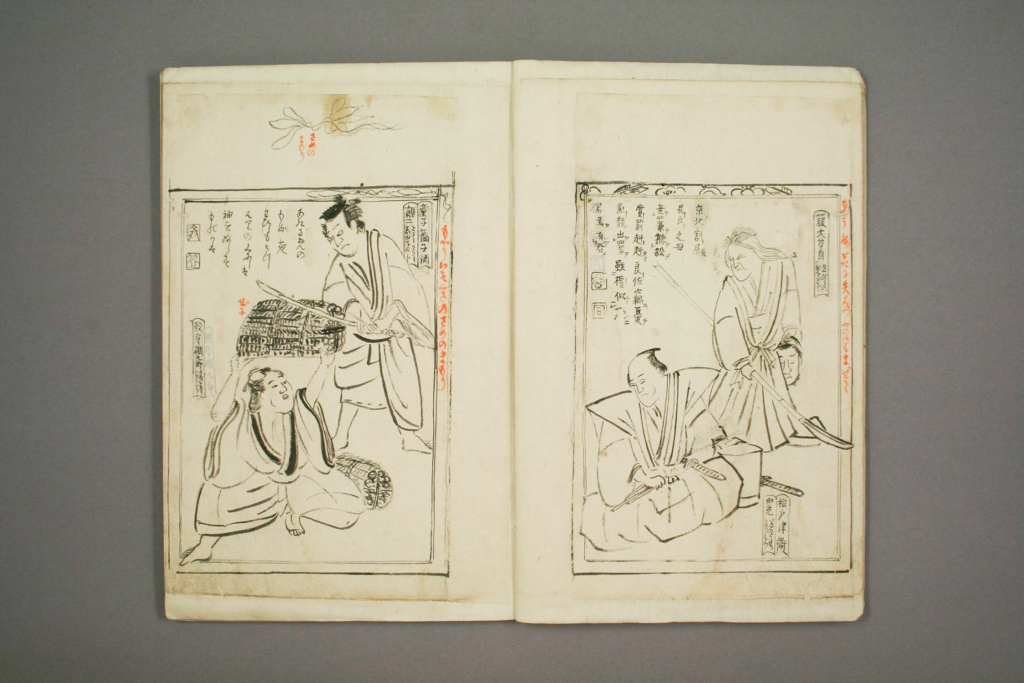

A Creative Partnership: Bakin and Katsushika Hokusai

Bakin’s career flourished during this period, and he collaborated with the renowned artist Katsushika Hokusai, who illustrated many of his works. Although their relationship was sometimes strained due to creative disagreements, their most famous collaboration, Chinsetsu Yumihari Tsuki (The Curious Tale of the Bow Moon), became a classic. This epic work, spanning five parts and 29 volumes, follows the adventures of a master archer who escapes to Izu Oshima after losing a war and eventually finds the Ryukyu Kingdom (modern-day Okinawa). Despite their successes, Bakin and Hokusai eventually parted ways for reasons that remain unclear, though some speculate it was due to a disagreement over a minor detail in the story.

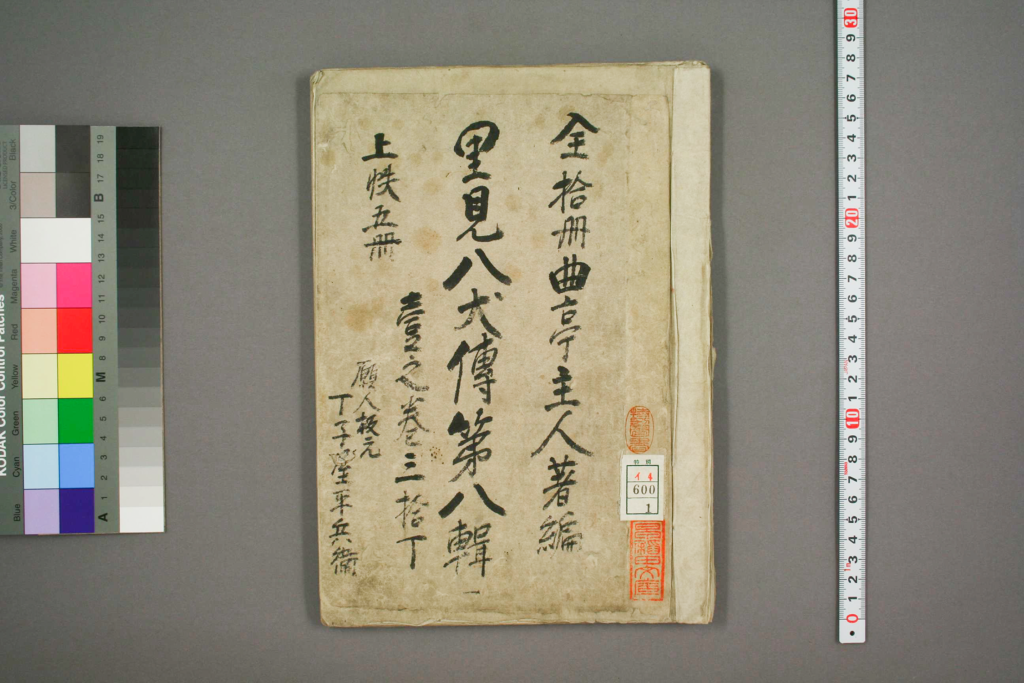

An Epic Legacy: Nanso Satomi Hakkenden

Bakin’s magnum opus, Nanso Satomi Hakkenden (The Eight Dog Chronicles), stands as one of the great literary achievements of Edo-period Japan. Drawing on Chinese folklore, Bakin spent 28 years completing this monumental work, which spans 98 volumes and 106 books. The story, set in the 1500s, follows eight warriors, each bearing a bead inscribed with a virtue, as they unite to restore the honor of Princess Fusehime’s fallen family. Blending human drama with fantastical elements, Hakkenden remains influential today, inspiring countless adaptations across various media. Bakin began the project at 48, enduring personal tragedies, including the loss of his son. In his later years, he went blind but continued the work by dictating it to his late son’s wife, finally completing the epic at the age of 76.

A Sweet Tooth and a Love for Birds

Bakin’s personal life had its quirks. Despite losing all his teeth by the age of 60, he maintained a love for sweets, particularly mizuame syrup, which he enjoyed throughout his life. He was also a dedicated bird lover, writing poetry about birds since childhood and even authoring a six-volume illustrated bird book. This work featured not only drawings but also in-depth knowledge of migratory species and rare birds that had strayed into Japan.

Journey to Kyoto: A City of Contrasts

Bakin’s travels to Kyoto left a lasting impression on him, and he documented his thoughts on the city’s culture. He praised the beauty of Kyoto’s women, the purity of the Kamo River’s water, and the majesty of its temples and shrines. However, he was less impressed with the stinginess of its people, the quality of its food, and the inefficiency of its shipping. His culinary critiques were particularly sharp, as he lamented the spoiled seafood due to Kyoto’s inland location, noting that only certain local dishes—like fu (wheat gluten), yuba (tofu skin), sweet potatoes, mizuna (potherb mustard), and udon noodles—were worth mentioning.

Bakin’s Legacy and Influence

Kyokutei Bakin’s influence on Japanese literature extends far beyond his lifetime. His works, particularly Nanso Satomi Hakkenden, left a profound impact on storytelling in Japan, weaving together themes of loyalty, honor, and the supernatural. He pioneered the system of full-time writing in an era when most authors treated it as a side profession. His dedication to his craft, even through personal tragedies and physical limitations like blindness, demonstrated his resilience and commitment to literature. Today, Bakin’s works continue to be studied, adapted, and appreciated, not just for their fantastical elements but for the depth of human emotions they explore. Whether through literature, stage performances, or modern media, Kyokutei Bakin’s legacy remains a cornerstone of Japanese culture.

.

.

.