Japan is renowned worldwide as a country steeped in a culture that combines both tradition and modernity. As an island nation with a 265-year history of isolation, many of the earlier aspects of Japanese culture developed completely unaffected by outside influences. Although Western culture has had a noticeable influence on Japanese society in more recent years, some aspects such as apprenticeship in a traditional Japanese craft remains inherently Japanese and still endures.

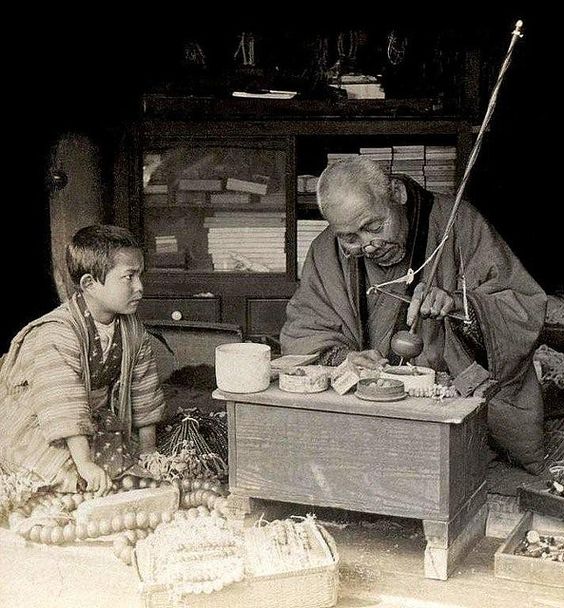

An apprenticeship in a traditional Japanese craft can be daunting for even the most dedicated student. Often lasting many years and with very few days off, the commitment requires unwavering effort and patience, without the guarantee of earning a lifelong livelihood upon completion. Traditional craftsmen usually start very young and spend several years simply doing menial tasks while observing the scope of the practice. And notice that I said “craftsmen” and not “craftswoman” or “craftsperson.” While it is true that the extent to which women could participate in Japanese society has varied over time and social classes, a large majority of the traditional Japanese crafts are still primarily dominated by men.

The young apprentices gradually take on small tasks followed by increasingly complex ones as they grow older and more capable. The emphasis of an apprenticeship is not on teaching, but on learning—observing and imitating, rather than being shown how. There is a Japanese concept known as gijutsu wo nusumu, which means stealing the knowledge. The masters (shisho) do not nurture their apprentices, but rather make them work for their knowledge. The idea is that people will place greater value on something they had to make an effort to learn.

For example, in the original 1984 Karate Kid film, the karate master Mr. Miyagi shows his young American student a number of moves (kata), but he refuses to explain one particularly difficult one, saying that it’s too advanced for him. Determined to learn the kata, Daniel-san carefully observes his teacher practicing it, then rehearses the move secretly on his own until he masters it. That specific kata enables him to win the decisive tournament in the end. Would Daniel-san have mastered the move as well if Mr. Miyagi had been willing to teach it to him? A traditional Japanese shisho would probably say no.

There are many Japanese crafts which involve devoting oneself to becoming an apprentice, and the practice spills over to the world of performing arts as well. Rakugo, is one such performing art which requires a lengthy apprenticeship.

Rakugo is the 400-year-old traditional art of Japanese storytelling. There are two regional styles of the art form, the Kamigata style and the Tokyo style. The Kamigata version is practiced in western Japan and centers around the city of Osaka. The Tokyo version, as the name implies, is limited to the Kanto region, or eastern Japan. Kamigata rakugo practitioners engage in an apprenticeship lasting three years. Their counterparts in Tokyo endure an apprenticeship program which can last a grueling 15 years.

Similar to other traditional Japanese crafts, in the highly disciplined world of rakugo, female storytellers (rakugoka) are scarce. In fact, the art form was developed and successfully dominated by men until 1993, the year when not one, but two women, Kokontei Kikuchiyo and Sanyutei Karuta, were promoted to the highest level possible (shinuchi). At the time of writing this article, there were approximately 1,000 professional storytellers in Japan. Women represent just one in 16 of those 1,000 rakugo artists.

But just as there are two styles of rakugo being performed today, there are also two classifications of rakugo performers, amateur and professional. Amateur storytellers known as tenguren date back to the Edo period and continue to flourish in the present day. They include students belonging to the Rakugo Kenkyu-kai (the rakugo study groups) at universities as well as performers hailing from all walks of life including teachers, office workers, housewives, and retirees, who enjoy performing rakugo.

The term tenguren is a relatively new word in the rakugo world. A tengu is a legendary creature with a long nose found in Japanese folklore, and it is strongly associated with vanity and pride. The Japanese expression tengu ni naru (becoming a tengu) is used to describe a person with too much pride. Amateur performers are often proud of their performances; therefore, they came to be called tenguren.

The advantage of pursuing amateur rakugo is that it does not require a long apprenticeship and is open to a larger percentage of women. Further, the amateur performers can continue to work while they perform rakugo and avoid the struggles many professional rakugoka face when it comes to making a living.

Despite not having to apprentice themselves, an amateur storyteller’s dedication and commitment to their art is still remarkable. Certain amateur performers show a high level of mastery that could rival some professionals. It is rather common for some rakugo fans to begin their journey by listening to amateur performers first and later gravitating toward professional performers. Therefore, we cannot ignore the role of amateur rakugo performers in the development of the art form and its diffusion overseas.

Interview with Female Rakugo Storyteller Kanariya Hotaru

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing an amateur female rakugo performer who belongs to the Kanariya rakugo performing family in Tokyo. She performs English rakugo regularly along with other students from the Canary English Rakugo School. This year, the school will celebrate its 15th anniversary.

Q: I understand that you hold a Ph.D. in Environmental Science and that you are currently working as a senior consultant for a prestigious actuarial and consulting firm in Tokyo. What drew you to rakugo?

I think rakugo is a vastly unique performance art. It involves a lone storyteller who conveys the story while sitting on a zabuton (floor cushion), wearing a kimono, and using only two props: a tenugui (hand towel) and a sensu (paper fan). The stories, many of which were developed over 100 years ago, are very interesting as well. Despite their age, they are still popular and still funny. Quite honestly, I started practicing rakugo in English as part of my English studies, but now I love rakugo in itself—including watching performances in Japanese. As you mentioned earlier, I work as a senior consultant, and I am mainly engaged in medical publication. I develop manuscripts to submit to medical journals within a team of healthcare and data analysts in the firm. This means I usually work quietly, so performing rakugo is quite a departure from my daily life. In terms of performing rakugo, I hadn’t performed in front of an audience since I was a primary school student. It gives me an opportunity to experience something that is very different from my daily life.

Q: How long have you been studying rakugo?

I have been studying rakugo for over 6 years.

Q: Do you perform primarily in English, or do you also perform in Japanese?

I perform only in English.

Q: What were some of the challenges you faced when you began to study rakugo?

First and foremost, it was very difficult for me to learn the story. In addition, I had to perform it in the rakugo-style. Everything was challenging for me in the beginning, and I experience some of those challenges even now.

Q: All rakugo performers have interesting stage names, names which are usually given to them by their rakugo masters. You have a unique and very pleasant stage name Hotaru (which means firefly in Japanese). Was this name chosen for you or did you select it on your own? If the latter is true, why did you choose this name? Does it have a special meaning for you?

I chose this name for myself. I was born and spent most of my life in the countryside in Hokkaido prefecture. Although, I had already left Hokkaido when I started studying rakugo, I wanted to give myself a suitable Hokkaido-like name. Hotaru is the name of one of the main characters in a famous old TV drama set in Hokkaido. I love that drama, and I think Hotaru is a Hokkaido-like name. So, for me, Hotaru means a woman from the countryside in Hokkaido.

Q: If I am not mistaken, you traveled to Laos with your rakugo master and another member of the Canary rakugo troupe in 2019. Was this the first time you performed rakugo in front of an entirely foreign audience? What was that experience like? How did it differ from performing in front of an all-Japanese audience?

Yes, I did perform rakugo in Laos, and it was the first time I performed in front of an entirely foreign audience. When our rakugo master asked me to participate in the tour, I was just really happy to be given such an opportunity. Gradually, however, I began to worry about whether I would be able to entertain the audience there with my performance. I was especially concerned about whether they would be able to understand my English. Of course, even in front of an all-Japanese audience, pronunciation is important. But while Japanese people are able to understand English spoken with a Japanese accent to some extent, foreign audiences are different. Before traveling, I practiced English pronunciation as well as the story I was planning to perform. In addition, I felt the burden of responsibility when it came to introducing rakugo as a member of the Canary English Rakugo School to an audience who was unfamiliar with what it was all about, and to make it an enjoyable experience for them. I felt nervous, but actually it turned out to be the same as performing in front of an all-Japanese audience. All in all, it proved to be a priceless experience for me, and this experience motivated me to want to become a better rakugo performer and to improve my English skills to better communicate with people in other countries.

Q: Given that rakugo is still dominated by male performers and there are few suitable stories for female storytellers to perform, do you have a favorite genre (e.g., stories about children, stories about men and women, fantasy and surrealistic stories, human interest stories)? If so, why do you favor that particular category?

I am in the process of trying to find out what types of stories are suitable for me to perform, and in that process, I have selected various types of stories to try out. I don’t believe I have a preference for a specific genre — I like stories that are silly and funny. My goal is to make the audience laugh so I focus on ways in which I could make them laugh. I think each performer, whether male or female, has their own ideas about how to make their audience laugh. I want to formulate my own ideas as well. In that regard, I am not too focused on gender. Regarding my preference for characters to portray, I think it is difficult to say exactly, but I enjoy playing women whose personalities are different from my own. This gives me the opportunity to venture into a world that is unfamiliar and that in itself is very satisfying.

Q: Rakugo storytellers perform alone on stage, and they must portray each and every character in the story. That is a lot to learn, even for a short story. Do you have a method by which you learn these stories? How long does it take you to learn a new story?

True, there is a lot to learn. I would also like some advice on how best to learn these stories. For me, it is difficult and time consuming to learn the dialogue. Once I learn it, I practice by repeating it while doing things such as washing dishes, walking outside, taking a bath, and so on. English is not my first language, so I have to repeat the lines over and over to get them to come out naturally. Recently, instead of memorizing each word in the script, I try to envision the scene in the story and imagine what the characters are saying. I think this method is much better when it comes to memorizing a story. In my case, it takes me a couple of months to memorize the lines, and then a few more months to really get it down incorporating the necessary action and facial expressions.

Q: What is your personal goal as a rakugo storyteller? What would you like to achieve?

Although I am a non-native English speaker, I have a desire to entertain audiences, particularly those in other countries with diverse cultural and historical backgrounds and different lifestyles. Rakugo is my vehicle by which to communicate with them. I want to improve my English and performance skills as well as understand more about rakugo itself. In time, I would like to develop my own style of performing rakugo and become a more effective entertainer. Rakugo is my hobby, but I think it is worth investing in to become better at it.

Q: What advice would you give to other female rakugo storytellers or to those women who are considering pursuing rakugo?

Honestly, I cannot think of anything specific to say to other female rakugo storytellers. I think each one has a different personality, and they pursue rakugo in their own unique style. I do not want to focus on gender necessarily, but rather their unique styles of performance. They serve as a reference for me when it comes to my own pursuit of rakugo, and they motivate me. For those who are considering pursuing rakugo for the first time, I recommend that they just give it a try. If they find that performing rakugo does not suit them, they can just quit. Since I started rakugo, I have become interested in various things such as kimono, and Japanese history and culture. I have met many different people and feel that my world has expanded. I would be happy if others could also discover something novel through rakugo.

Some of the stories that the students of the Canary English Rakugo School perform can be found in their entirety in a book that was recently released by the school’s founder, Kanariya Eiraku. The book, Eiraku’s 100 English Rakugo Scripts: Volume 1 (ISBN: 978-1088061688), is available on Amazon and other major online book retailer’s websites.

『Kristine’s Eye on Japan: Introduction to Japanese Culture』

Writer: Kristine Ohkubo

.

(9/12/2022)