In Japan’s historic timekeeping system, the length of an hour changed daily

Isolated for centuries while the rest of the world was industrializing, Japan developed many unique ways of living. One of the strangest to our modern thinking was a system for counting time where the length of an hour changed daily.

The way of counting time used everywhere now is called a “fixed hour system.” Each day has 24 hours, and each hour is the same length of time. We further divide each hour into 60 minutes of 60 seconds, derived from Babylonian numerology.

A fixed time system is well suited to mechanical (and now electrical) time counting devices — clocks. A clock uses either a pendulum or spring (and now quartz crystals) to mark fixed amounts of time. Add the right set of gears (or chips) and it’s easy to count the minutes and hours of the day.

Since we’ve lived with a fixed time system all our lives, we assume this is the only way to divide time.

However, in an unmechanized, agrarian society, a set amount of time per hour isn’t the most obvious way to count time. For a farmer, daytime is the time between sunrise and sunset, night is the time when it’s dark.

It’s natural to divide daytime into a few separate periods: early morning, mid-morning, noon, early afternoon, mid-afternoon, sunset. And this is exactly how Japan’s time system worked.

What mattered was not some fixed amount of time, but where we were in the day. Of course, as the length of the day changed daily, the length of each period also expanded and contracted. But mid-morning was always 2/3 of the time from daybreak until noon.

This unfixed time system, called futeijihō (不定時法) in Japanese, is also called the “temporal hour system” or “seasonal time system.”

Japan’s unfixed time was used for hundreds of years during the Edo Period until the modernization of the Meiji Era. Here’s how it worked:

Japan’s Unfixed Time

Based on the Chinese horoscope, a day was divided into 12 segments, each called an ittoki (一刻, one toki).

(Note: while 一刻 is read now as ikkoku, it was ittoki then.)

Daytime — the time between sunrise and sunset — was divided into 6 toki. Nighttime — from sunset until dawn — was separately divided into 6 toki.

At the spring and autumnal equinox, the length of day and night is the same. But during the summer, the day is long, and in winter, the sun sets early and rises late.

Consequently, the length of each toki is different between day and night. It also depends on the day of the year and on the latitude, which varys widely across Japan.

Still, without mechanized timekeeping, this ittoki system was easy to understand. People only needed to divide the day evenly. Six toki during the day meant 3 toki from dawn until noon, then 3 more toki until sunset.

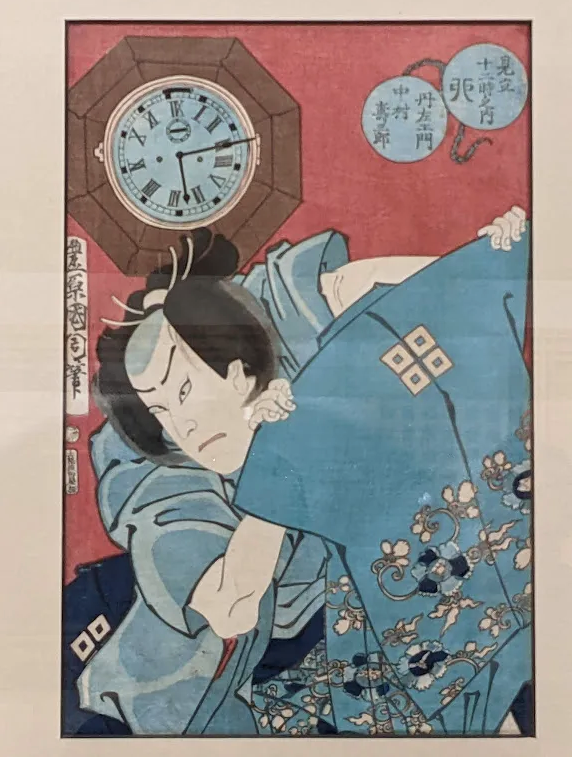

Confusingly though, instead of simply counting from 0–12, toki were counted down from 9 to 4, twice each day. The numbers 1–3 couldn’t be used because they referred to Buddhist prayer times. Toki were counted down instead of up because before clocks arrived, special incense sticks were used to count down the time as it burned.

The Chinese zodiac animals were also used to describe the hour. Midnight was ne no koku (子の刻 — hour of the rat). People believed ghosts would appear during ushi no koku (丑の刻 — hour of the ox), roughly 2 AM. To place a curse on someone, you visited a shrine at the time of ushi no koku and nailed a straw doll to a tree.

We still use the word oyatsu (お八つ) to refer to an afternoon snack. The word literally means 8, because 8 toki was early afternoon, roughly 2 PM.

The First Clocks in Japan

So what happened when Christian missionaries and traders brought mechanical clocks into Japan?

In 1551, Francis Xavier sent a mechanical clock to the daimyo of Suo Province (Yamaguchi Prefecture). A spring-driven clock was given to the Shogun, Ieyasu Tokugawa, in 1612.

Blacksmiths in Japan started manufacturing clocks and became known as “tokeishi (時計師)” — clock makers. Most Japanese clocks were made in the shape of a lantern called a Yagura-dokei 櫓時計 or a tower called a Dai-dokei 台時計.

But instead of converting Japan to fixed mechanical time, these clock makers came up with ingenious ways of adjusting the mechanical clocks for Japan’s unfixed time.

There are 2 possible ways to adjust the clock mechanism for non-constant time: either change the speed of the clock by moving weights, or change the location of hour marks on the dial.

If you’re interested in the mechanical details, this page on the website of the Japan Clock & Watch Association shows how they worked. This lantern clock at the Matsumoto Timepiece Museum has 2 sets of weights at the top to adjust separately for day and night.

Telling Time in Tokyo

As the Edo Period progressed, the government became more bureaucratic, and commerce and trade expanded. And that meant — meetings! Which needed a better way to describe time than “meet me at my shop mid-afternoon.” Employees had to know when to arrive at work, too.

But switching to a fixed hour system would have required a complete shift in how people thought of time. Instead, what developed organically over hundreds of years was a complex system to announce the time to the population.

Castles had a clock room called a tokei-no-ma (時計間) where a clock was kept. From there, each toki was announced to the surrounding area using large bells.

The capital of Edo, the largest city in the world at the time, had 9 bells at shrines and temples spread around the town. The bells were struck in a fixed order from one site to the next to announce the time across the entire area. A warning bell was rung 3 times before the official bell to notify the next bell ringer to get ready.

By the middle of the 17th century, this time notification system was extended across the entire country so that everyone knew the time. Who needs clocks when we have underemployed bureaucrats?

Incense clocks were also used to measure the time between bells. Though they burned at a fixed speed, they could be adjusted by cutting to the appropriate length for each day.

The End of Toki Time

In 1868, during the turbulence of the early Meiji Era, laws were passed promoting native Shinto over Buddhism. Bells were considered Buddhist since they were used to call monks to prayer. Bells had to be removed from Shinto shrines, interrupting the time announcement system.

A few years later, in 1873, the government completely reformed the calendar, switching to the Gregorian solar calendar and a 24 hour fixed time day.

With access to technology from all over the world, the country began rapid industrialization. Modern life advanced. People left farms to work in the cities where they lived in homes with lighting. Time based on sunrise and sunset became less useful than the precise timekeeping needed to operate factories and run trains according to a schedule.

Now with our smartphones, we have time accurate to the millisecond in the palm of our hands. But as I dash from one meeting to the next, desperate not to be even a minute late, I wonder what life was like when time was as simple as measuring each toki with an incense stick and listening for the temple bells.

If you want to learn more about time and timekeeping or just appreciate the complexity of antique clocks, I heartily recommend a visit to the Matsumoto Timepiece Museum in Matsumoto, or the Seiko Museum in Ginza, Tokyo.

References:

https://matsu-haku.com/tokei/

https://www.jcwa.or.jp/etc/wadokei.html

https://museum.seiko.co.jp/knowledge/relation_07/

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/和時計

https://eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/koyomi/wiki/BBFEB9EF2FC4EABBFECBA1A4C8C9D4C4EABBFECBA1.html

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/丑の刻参り

・・・

If you enjoy my articles, you’ll love my novel of Japanese culture in Silicon Valley. To Kill a Unicorn is the story of a Japanese-American in Silicon Valley (which was originally a Japanese farming community) who uses tea ceremony, sake, and Japanese whiskey (a bit too much) to find his missing friend. Pre-order your copy now!

.

『Learn Japan Deeply with DC!』

Writer: DC Palter

Read DC’s Stories More at Japonica Publication ( medium.com/japonica-publication )

(3/6/2023)

.

.